By Harris Meyer, KFF Health News

As regulators review Kaiser Permanente’s proposed acquisition of a respected health system based in Pennsylvania, health care experts are still puzzling over how the surprise deal, announced in April, could fulfill the managed care giant’s promise of improving care and reducing costs for patients, including in its home state of California.

KP said it would acquire Danville, Pennsylvania-based Geisinger — which has 10 hospitals, 1,700 employed physicians, and a 600,000-member health plan in three states — as the first step in the creation of a new national health care organization called Risant Health. Oakland-based Kaiser Permanente said it expects to invest $5 billion in Risant over the next five years, and to add as many as six more nonprofit health systems during that period.

Industry experts believe KP’s aim is to build a big enough presence across the country to effectively compete with players like Amazon, Aetna CVS Health, Walmart Health, and UnitedHealth Group in providing health care for large corporate customers. Kaiser Permanente executives touted the potential for spreading the group’s vaunted brand of quality, lower-cost care around the country.

But it’s not clear how KP will be able to bring its model, in which facilities and doctors receive a monthly per-member fee for all care, to markets where it doesn’t own an integrated system of physicians, hospitals, and health plans, as it does in California. Critics note that KP’s efforts to expand failed in a number of states in the 1980s and 1990s.

In addition, the physician-led Permanente Medical Groups, which lead KP’s patient care, were not involved in the Risant deal, raising questions about how their expertise would be shared.

“I don’t know how Kaiser will bring its knowledge and best practices to improve health care delivery without the involvement of the medical group, which does all the care delivery,” said Robert Pearl, a former CEO of the Permanente Medical Group who’s now a lecturer at the Stanford Graduate School of Business.

Is Bigger Better?

There are also questions about how the expansion will benefit current KP customers. The tax-exempt, nonprofit organization has 39 hospitals, 24,000 physicians, and 12.7 million health plan members in eight states and Washington, D.C., though about three-quarters of its members are in California, where it controls nearly half of the private insurance market. KP reported $95 billion in revenue last year.

“We’ve asked Kaiser Permanente management questions about the deal’s advantages to employees and customers, but we haven’t heard back,” said Caroline Lucas, the executive director of the Coalition of Kaiser Permanente Unions, several of which are in contentious contract talks with the company. “Where is the money coming from? Are the citizens of California and other states subsidizing this expansion? How are they benefiting?”

Kaiser Permanente CEO Greg Adams declined to comment. A KP spokesperson, Steve Shivinsky, said the group’s physicians would be involved in developing a “platform” to offer other health systems its value-based care expertise, including in design of care models, pharmacy practices, consumer digital engagement, development of health insurance products, and best practices for supply chains. Shivinsky said work on the platform was just beginning.

“Risant Health’s success will firmly establish value-based care as a better model for health care in this country,” said Shivinsky, KP’s director of national media relations.

“If there is a commitment to truly delivering higher-quality and lower-cost care, it will take time and hard work,” said John Toussaint, chair of Catalysis, a nonprofit that trains executives in health care and other industries in quality improvement. “But frankly I’m skeptical that’s the reason for these types of mergers. Bigger may be better for increasing prices, but not necessarily for improving care.”

The deal may be a sign that KP, founded in 1945, is hearing the alluring call of lucrative fee-for-service medicine. “This gets Kaiser into the much bigger part of the market — commercial insurance — and expands beyond their traditional model of owning all the pieces and selling their own insurance,” said Glenn Melnick, a health economics professor at the University of Southern California.

The Geisinger acquisition is being reviewed by the Pennsylvania Insurance Department, with a 30-day public comment period ending Aug. 7, 2023. The Federal Trade Commission and the California attorney general’s office declined to say whether they were reviewing the deal. KP expects the deal to close sometime in 2024. There was no purchase price, but KP said Risant would make a minimum of $2 billion available to Geisinger through 2028, including income that Geisinger generates itself.

Federal and state antitrust regulators have expressed growing concern about consolidation of hospitals and physician groups into ever-larger organizations with the power to drive up prices. But antitrust experts say it’s unlikely regulators will challenge the deal since KP does not currently have a presence in Pennsylvania, Delaware, or Maine, where Geisinger operates.

Indeed, the deal could boost competition if KP’s investment enables Geisinger to expand beyond central and eastern Pennsylvania and take on the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center and Highmark, the state’s two dominant integrated health systems.

Around the country, Risant could be appealing to businesses that offer health plans to their employees.

“If Kaiser can become an effective player in more markets through Risant and that leads to greater price competition, that will be very attractive to large employers,” said Bill Kramer, senior adviser for health policy at the Purchaser Business Group on Health, which represents large employer health plans.

Smaller health systems and physician groups that are struggling financially may also see joining Risant as a more palatable option than being acquired by more profit-hungry entities, such as private equity firms, Melnick noted.

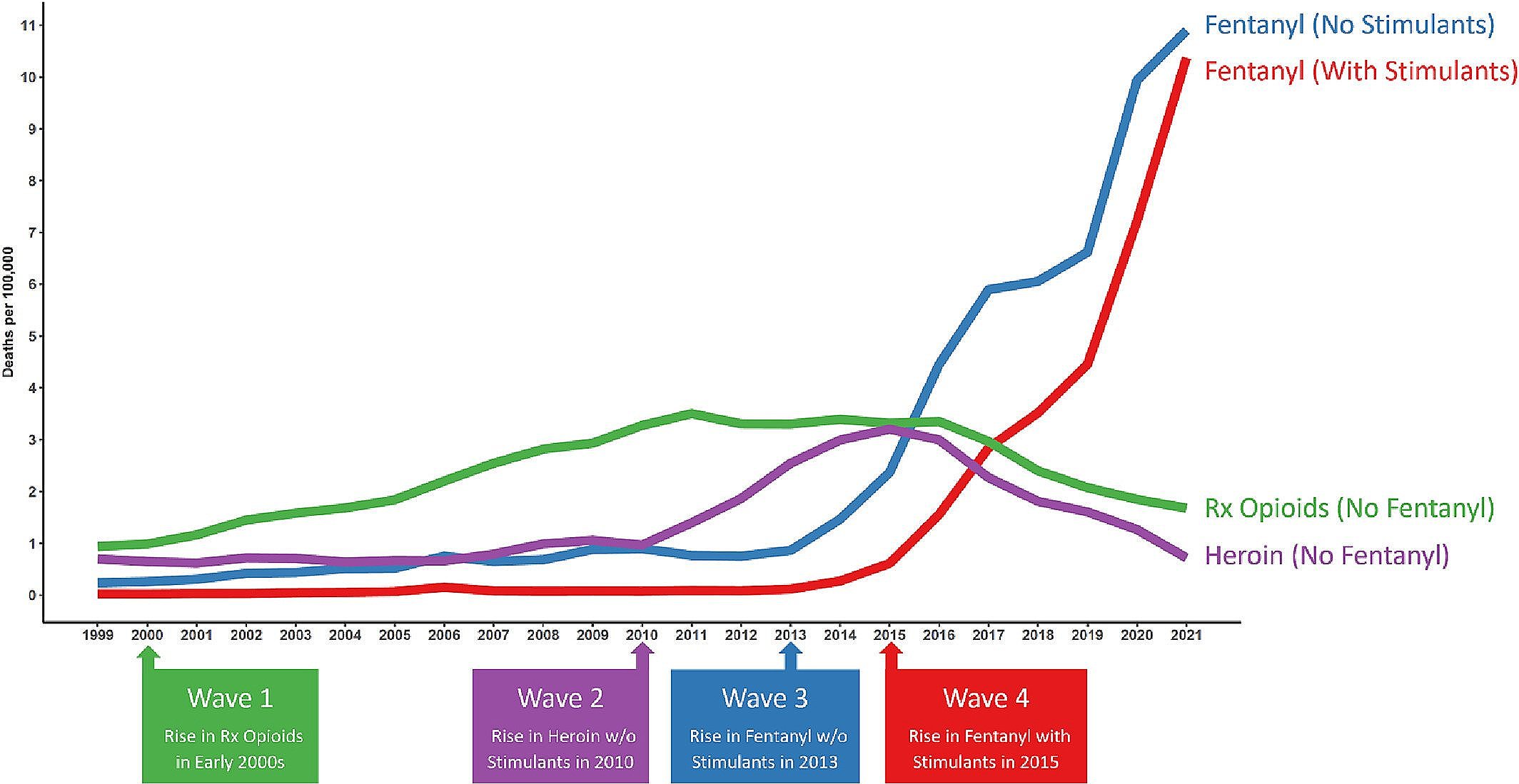

Through tight coordination between its physicians, hospitals, and health plans, KP has a strong track record of producing good health outcomes, particularly for plan members with chronic conditions such as high blood pressure and diabetes. In recent years, Kaiser doctors have also significantly reduced opioid prescribing.

KP hospitals and doctors are paid a monthly per-member fee for all care — called capitated payment. That gives KP a powerful financial incentive to keep members healthy and prevent costly hospital admissions and emergency room visits.

In contrast, Geisinger and most other health systems across the country generally are paid for each separate procedure — known as fee-for-service payment — giving them less incentive to keep patients healthy and reduce overall costs. Because of that, it’s not clear how KP’s value-based care model will work at Geisinger and other health systems acquired through Risant.

Adams has said Risant won’t try to fully replicate Kaiser Permanente’s model. Instead, Risant will help other health systems achieve the same kind of outcomes and cost savings while working with multiple insurers and providers.

KP also could potentially learn lessons from Geisinger and other health systems about producing better health outcomes at lower cost for members. Geisinger has won acclaim for its ProvenCare model, in which it accepts a fixed fee for providing an entire episode of care, such as heart bypass surgery, with no extra charge if the outcome isn’t satisfactory and the patient needs additional care.

But Kramer, a former KP executive, is skeptical. “It’s hard if not impossible to transform a medical group that’s reliant on fee-for-service payment into something like the Kaiser Permanente Medical Group,” he said.

Critics of the deal, citing KP’s failed expansion moves in the 1980s and 1990s, also worry that building Risant Health could distract KP executives from cost-control and quality improvement efforts in their home state and draw down the organization’s financial reserves, potentially leading to premium hikes.

In 1999, for example, KP sold a money-losing medical group it had established in North Carolina in the mid-’80s. It faced opposition from the local medical community and challenges with employer health plans, among other factors. Kramer also pointed to its withdrawal from other markets including Connecticut, Missouri, Ohio, and Texas.

Still, KP did succeed in establishing a significant presence in the mid-Atlantic states, Washington, D.C., and Georgia, though it doesn’t own hospitals in those markets. It also has long-standing operations in Hawaii, Colorado, and Oregon.

With Risant, KP will be up against very large, sophisticated managed care competitors including UnitedHealth’s Optum, which employs about 70,000 physicians across the country.

“Hopefully Kaiser’s senior leadership will be smarter this time around and avoid the kinds of problems they had when they expanded in the past,” Kramer said.

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues. It is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.