CDC Is Worried About Shortages of ADHD Stimulants. What About Rx Opioids?

/By Pat Anson

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is worried that shortages of stimulant medication used to treat attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) may be forcing some patients to turn to street drugs or even suicide.

In a new report, the CDC estimates that 15.5 million U.S. adults have ADHD¸ a condition that causes inattention, impulsiveness and hyperactivity. About a third of those patients were prescribed a stimulant, but 71.5% of them had difficulty getting their prescription filled because of shortages.

“Shortages of stimulant medications in the United States have affected many persons with ADHD who rely on pharmacotherapy to appropriately treat their ADHD,” wrote lead author Brooke Staley, PhD, an epidemiologist at the CDC’s National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities.

“Patients experiencing these difficulties might seek medication outside the regulated health care system, increasing their risk for overdose because of the prevalence of counterfeit pills in the illegal drug market, which might contain unexpected substances such as fentanyl.”

This is the second CDC report in recent months to warn about stimulant shortages. In a CDC Health Advisory released in June, the agency said ADHD patients who are unable to obtain Adderall and other stimulants are at risk of “social and emotional impairment, increased risk of drug or alcohol use disorder, unintentional injuries, such as motor vehicle crashes, and suicide.”

The CDC’s concern about ADHD patients is in marked contrast to its ongoing neglect of pain patients, who face similar shortages of opioid medication.

In a recent PNN survey, 90% of pain patients said they experienced delays or problems getting their opioid prescriptions filled at a pharmacy. Desperate for relief, some bought counterfeit medication or other illicit drugs; obtained opioids prescribed to another person; or used alcohol, cannabis and other substances to ease their pain. Nearly a third said they considered suicide because their pain was so severe.

In short, the very same risky behavior that concerns the CDC about ADHD patients.

We asked the CDC if it was studying the impact of opioid shortages on pain patients and instead got a defense of the ADHD study.

“There has been limited information about (ADHD) diagnosis and treatment in adults and this analysis aimed to fill that information gap – providing the first national estimates on prevalence of adult ADHD in more than a decade. It is also the first national estimates to describe age at diagnosis and treatment, including telehealth and difficulty filling stimulant prescriptions,” a spokesperson said in an email.

It would not be unreasonable to say that the CDC shares some of the blame for chronic shortages of hydrocodone, oxycodone and other prescription opioids. The agency’s controversial 2016 opioid guideline paved the way for steep cuts in opioid prescribing, resulting in “serious harm” to patients who were rapidly tapered and left in uncontrolled pain. Some committed suicide.

The CDC guideline also greased the skids of opioid litigation by exaggerating the risk of opioid addiction and overdose. Faced with a tsunami of lawsuits, drug distributors and pharmacy chains agreed to ration the supply of opioids at individual pharmacies, and drug makers cut back on the production of opioids to avoid further liability. As recently as last month, Teva Pharmaceuticals stopped production of immediate-release fentanyl medicines, potent pain relievers that were relied on by dying cancer patients.

The CDC has been silent about opioid shortages – so have the FDA and DEA.

“We don't make the medicines and we can't tell someone that they must make medicines. There are some things that are out of our control,” FDA Commissioner Robert Califf, MD, said in a 2023 interview.

Faced with complaints about shortages of ADHD medication, the DEA recently said it would raise the supply of stimulants that drug makers are allowed to produce in 2025, but would continue with its decade-long campaign to reduce the supply of opioids.

That discrepancy hasn’t been lost on pain sufferers.

“You’ve corrected course for ADHD drugs, now do the same for opioid pain analgesics,” one patient posted in a comment on the DEA’s plan. “Do not cut opioids production in 2025. The shortages across the country will be worse, with a corresponding increase in suffering and deaths among chronic pain patients.”

“These proposals will only further the pain and harm on a community of disabled individuals that did not ask to be disabled,” wrote Rebecca Meadows. “Would you want your mother, brother, sister, child or yourself to suffer unnecessarily due to unwarranted cutbacks in pain medications being made? The amount of people who suffer now is ridiculous but it’s only going to get worse if we continue on this path.”

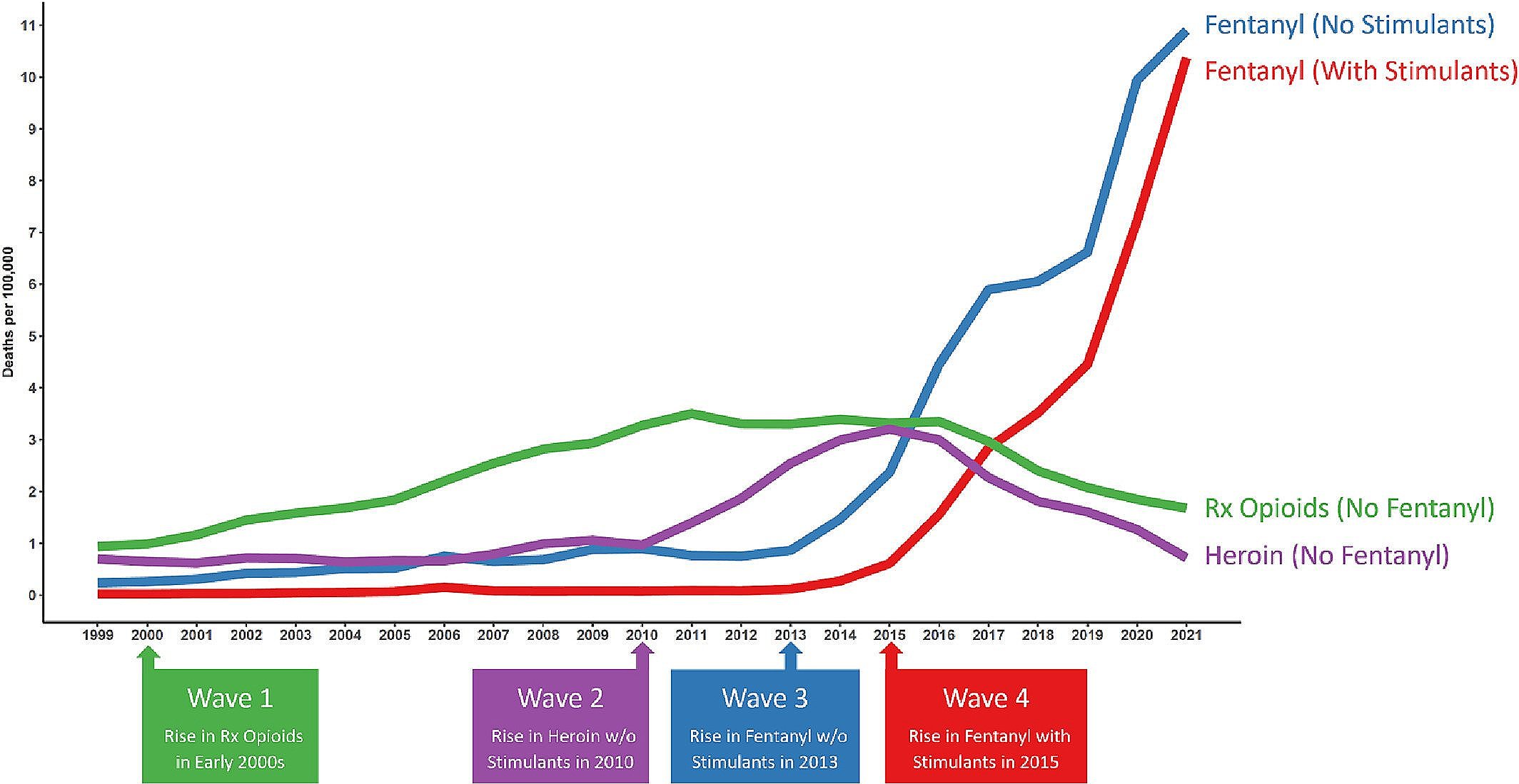

A former CDC epidemiologist wrote a book about how the CDC’s “Disastrous War on Opioids” made the overdose crisis worse. Opioid overdoses have nearly doubled since the 2016 guideline was released.

“There are still significant restrictions on people in chronic pain for no apparent benefit. There continues to be very high rate of overdoses,” said author Charles LeBaron, MD. “I'm kind of a diehard public health guy. I want to see whether anything good happens. Nothing good happened. Time to reconsider.”