Safer Opioid Supply Helps Reduce Overdoses

/By Pat Anson

Should people at high risk of an overdose be prescribed opioids like hydromorphone or should they get methadone to help them cope with opioid addiction?

It’s a controversial question in Canada, where harm reduction programs are being used to give high-risk drug users a “safer supply” of legal pain medications as an alternative to increasingly more toxic and deadly street drugs. Critics say safer opioid supply (SOS) programs don’t reduce overdoses and are a risky alternative to more traditional addiction treatment drugs like methadone.

A new study, however, found that SOS programs are just as effective as methadone and may even be safer in the long run. Researchers in Ontario followed the health outcomes of over 900 people newly enrolled in SOS programs, comparing them with a similar number of drug users who started methadone treatment.

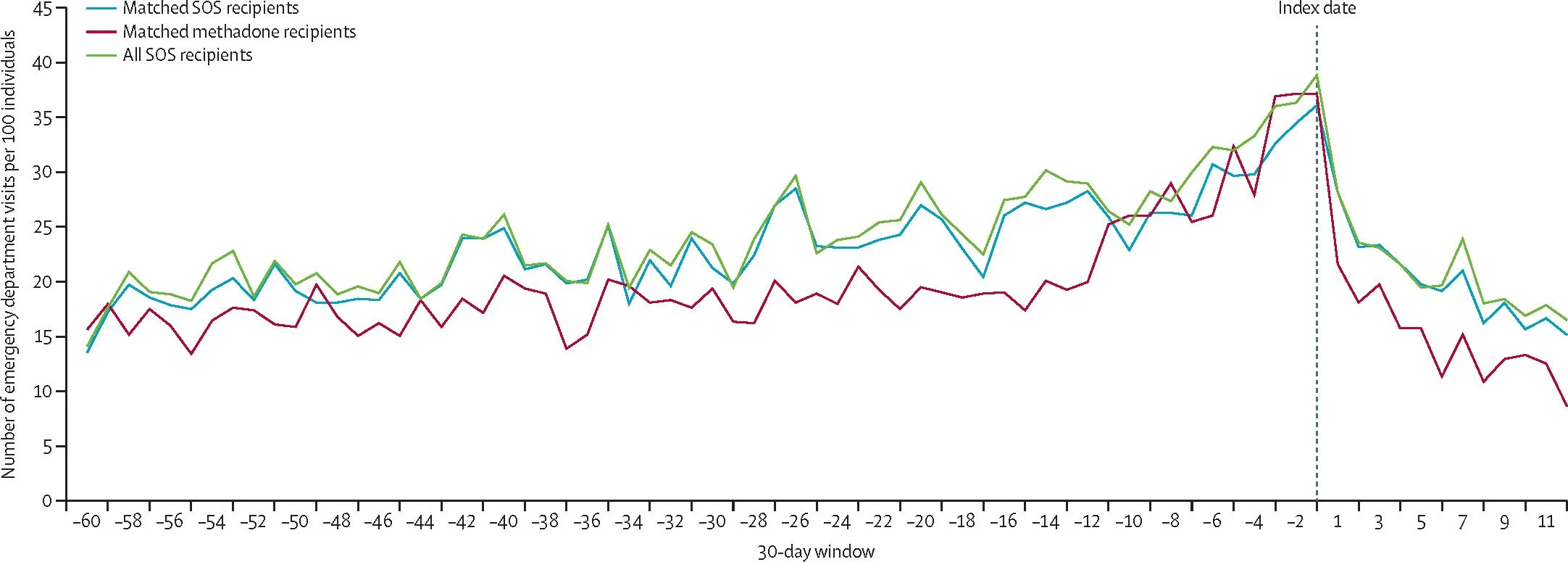

Their findings, published in The Lancet Public Health, show that people in both the SOS and methadone groups had significant declines in overdoses, emergency department (ED) visits, hospitalizations, severe infections, and health care costs in the year after they started treatment. In both groups, deaths related to opioids or any other cause were uncommon.

ED Visits Fell After High-Risk Drug Users Enrolled in SOS or Methadone Programs

THE LANCET PUBLIC HEALTH

"This is the first population-based study to compare SOS programs with opioid agonist treatment, and to explore how people's outcomes change in the year after initiation," said lead author Tara Gomes, PhD, an epidemiologist and Principal Investigator at the Ontario Drug Policy Research Network (ODPRN).

Gomes and her colleagues found that people on methadone had a slightly lower risk of an overdose or being admitted to hospital, but they were also more likely to discontinue treatment and be at risk of a relapse. The higher dropout rate outweighed most of the benefits of methadone over SOS.

"Neither methadone nor safer supply programs are a one-size-fits-all solution, but our findings show that both are effective at reducing overdose and improving health outcomes," said Gomes. "They are complementary to each other, and for many people who haven't found success with traditional treatments like methadone, safer supply programs offer a lifeline. Our findings show that when safer supply programs are implemented, we see fewer hospital visits, fewer infections, and fewer overdoses."

SOS programs were launched in Ontario and British Columbia to combat a rising tide of overdoses linked to illicit fentanyl. A decade ago, Vancouver was the first major North American city to be hit by a wave of fentanyl overdoses, which led Vancouver to become a laboratory for harm reduction and safe injection sites that provided heroin or prescription opioids to drug users.

The results have been somewhat mixed. An investigation by the National Post found that hydromorphone pills given to drug users in Vancouver were being sold on the black market, with the sellers then using the money to buy street drugs. Complaints about people selling their safe supply drugs led to British Columbia’s Health Minister recently changing the rules so that the SOS drugs are consumed while under the supervision of a pharmacists or healthcare provider.

A 2024 study in JAMA Internal Medicine found that opioid-related hospitalizations rose sharply in British Columbia after harm reduction programs were launched there, although there was no significant change in overdose deaths. The spike in hospitalizations may have been due to more toxic street drugs and counterfeit pills on the black market.