A Pain Patient's Perspective on Opioid Prescribing

/By Barby Ingle, PNN Columnist

It is essential to prescribe pain treatments that are appropriate and effective for each patient. I say that based on my own experiences as a patient, as well as thousands of others I have spoken with over the years as a friend and advocate.

Patients who need opioids, benzodiazepines, antidepressants and other medications should have access to them -- just as a heart patient has access to medication that keeps their heart functioning or a diabetic needs access to insulin.

People living with pain should also be offered individualized treatment. That could be anything from physical therapy and analgesics to surgical procedures and alternative therapies like acupuncture. I have tried over 100 different types of pain treatment; some have worked and others have not. It often made me feel like a guinea pig. Unnecessary surgery hurt me most in the end.

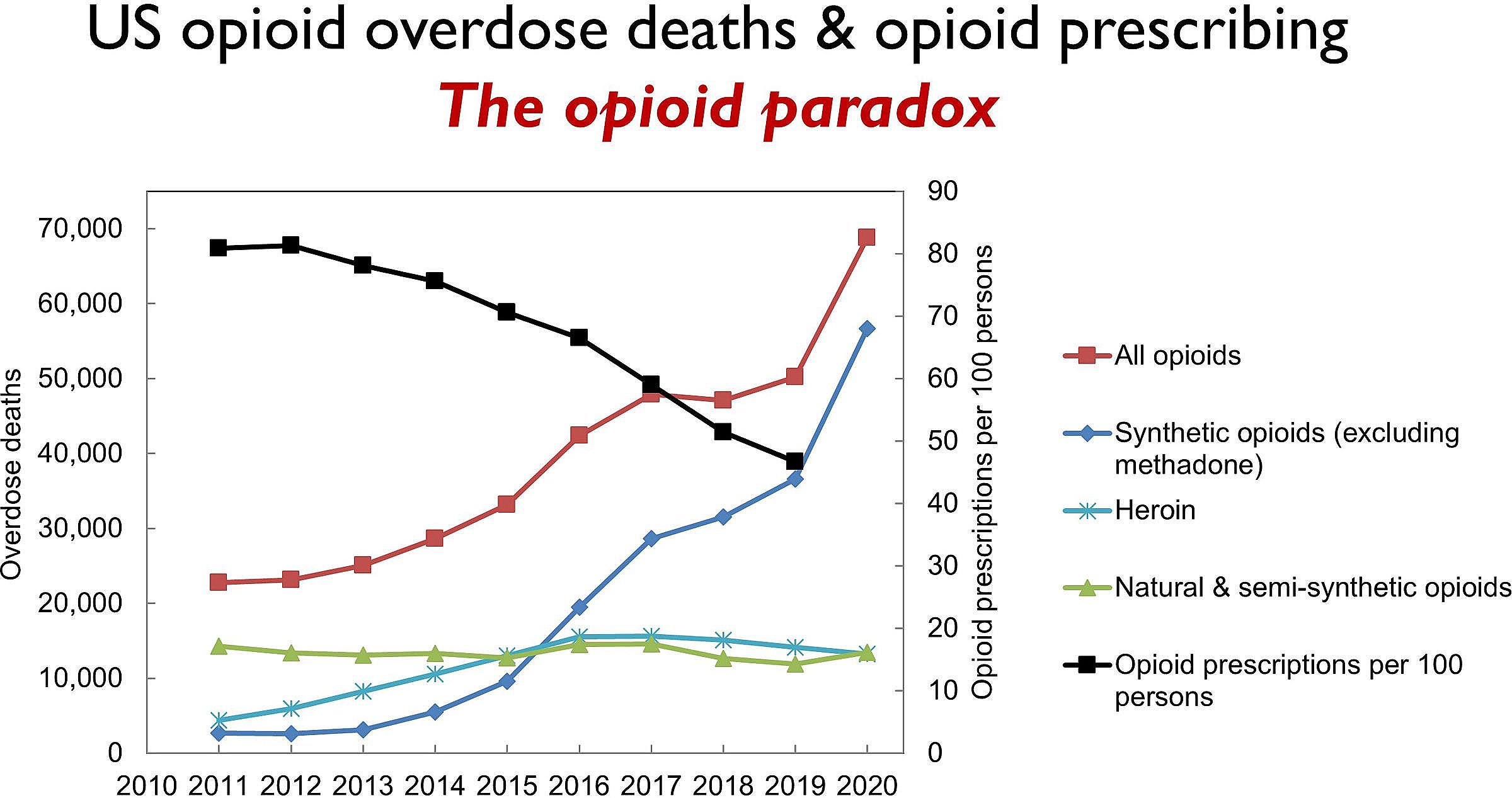

There are many public education campaigns underway to prevent addiction and overdoses by reducing the use of prescription opioids. These campaigns are repeated in the media, but the information does not always include facts or is presented in a misleading way.

For example, there is the DEA’s “One Pill Can Kill” campaign, which is aimed at raising awareness about a surge in counterfeit pills made with illicit fentanyl and other street drugs. Another is the CDC’s “Rx Awareness” campaign, which shares the stories of people whose lives were impacted by prescription opioids. The overall theme is that opioids are “addictive and dangerous.”

Although well-intentioned, these campaigns have a tendency to demonize FDA-approved medications that have a lot of science and research behind them. Most people are unaware that fentanyl has been used safely and effectively for decades to treat severe pain and as an analgesic in millions of surgeries. Saying “one pill can kill” to a pain patient who has improved their life with a legally prescribed medication is disheartening.

I have seen this misinformation firsthand over the years and how it has put a damper on opioid prescribing. Physicians should prescribe opioids for pain when appropriate, but many are afraid to do so because of potential sanctions and legal threats. As a result, many providers won’t prescribe opioids or will only do so minimally and as a last resort.

Individualized Treatment

I believe each patient is different and should be treated as such. We need providers to operate on the assumption that each individual is unique and requires something different, even when they have the same disease or injury as someone else.

Physicians today can use pharmacogenomics to see if a patient’s DNA can affect how they respond to a treatment or what is chemically right for them. The dosage, brand, procedure and frequency will vary depending on each patient. I often bring my pharmacogenomics information to communicate more effectively with my providers, which benefits us both.

I also know that doing what is least invasive first and then progressing to other options is essential. Sometimes, surgery is the best option. Sometimes, opioids or other pain medications should be used first. Every medical provider should work at finding the treatment that most effectively suits the patient.

It is a considered best practice to prescribe opioids to someone in severe pain from sickle cell disease. Yet, when many sickle cell patients go to the ER or are admitted to a hospital, they are denied opioids because of hospital policy. What is the point of having a trained medical providers on staff if you won’t let them treat a patient the way they should be?

Denying pain relief is not only cruel, it can be the worst practice for everyone involved. For example, a man in severe chronic pain committed suicide after a doctor at a Kentucky pain clinic cut his opioid dose in half. The man’s family filed a lawsuit and won a $7 million judgement against the doctor and clinic.

Ultimately, it should be the patient's responsibility to weigh the risks and benefits of any treatment, after getting input from their provider and conducting due diligence. Unfortunately, there are many obstacles standing in the way of that. One of the biggest is finding a doctor willing to prescribe pain medication. In addition, there are insurance restrictions, the cost of medication, and other logistical issues such as transportation to appointments.

Here in Arizona, patients must see their provider every month to renew a prescription for a controlled substance. Policies like that were put in place to “protect” pain patients, but only added extra costs, burdens and stigmas to them.

Patient-Physician Communication

How can we change the narrative about opioid prescribing? We can start by emphasizing the importance of effective communication between physicians and patients, even those as young as elementary school. Early education on how to talk to medical professionals and advocate for yourself is vital. I see this as one of the most critical things for patients to do.

Communication and trust are essential. Patients need to know when to take medication, how much to take, and what the potential side effects are. They also need to be able to express how the medication is working and what their symptoms are. Patients should feel comfortable asking questions and discussing their pain management plan. Physicians need to listen, provide feedback and give advice when needed.

Individualized treatment plans should be tailored to the patient’s age, gender, medical history, lifestyle and other factors. That will help ensure that the treatment is effective and also reduce the risk of adverse reactions and potential complications. Collaborative decision-making makes patients feel more comfortable, confident in their treatment plan, and more likely to follow it.

Barby Ingle is a reality TV personality living with multiple rare and chronic diseases. She is a chronic pain educator, patient advocate, motivational speaker, and the founder and former President of the International Pain Foundation. You can follow Barby at www.barbyingle.com.