60 Minutes Fails to Consider Pain Patients

/By Laura Mills, Kate M. Nicholson, and Lindsay Baran

In a Feb. 24 segment, CBS’s 60 Minutes accused the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) of igniting the overdose epidemic in the United States with its “illegal approval of opioids for the treatment of chronic pain.” While the program highlighted the adverse consequences of misleading pharmaceutical marketing and lax government oversight, this segment failed to consider the perspective of patients who legitimately use opioids for pain, stigmatized them as drug-seekers, and propagated misconceptions about the overdose crisis, such as the idea that opioid treatment for chronic pain is indisputably illegitimate and is driving overdose deaths in the U.S.

When OxyContin went to market in 1996, its FDA label said that addiction was “very rare” when the medication was used to manage chronic pain. Although that warning was enhanced in 2001, the market for OxyContin was already booming: advertising spending for the drug increased from $700,000 in 1996 to $4.6 million in 2001. Lawsuits allege that Purdue Pharma, the maker of the drug, targeted high-prescribing physicians and continued to aggressively market OxyContin even after it learned its product had become a go-to drug for illicit use. The lack of government oversight and Purdue’s practices certainly deserve media scrutiny that could help shed light on actions that may underlie the overdose crisis.

However, the guests featured in the 60 Minutes segment gave the impression that the use of opioids for chronic pain is illegitimate or illegal, that prescription opioids are still driving overdose deaths in the United States, and that the use of prescribed opioids to manage chronic pain is equivalent to “heroin addiction.”

These are false narratives that do real harm to pain patients, who have been regularly stigmatized in the media and elsewhere as drug-seekers. In presenting this report, 60 Minutes failed to tell the other side of the story: that of pain patients who rely on these medications to function, and that of the medical community which largely agrees that opioids may help patients whose pain isn’t resolved by other means.

Chronic pain is a large category that includes pain associated with incurable illnesses, severe neurological conditions, and catastrophic trauma as well as more common ailments like arthritis. There is growing agreement that using opioids across this broad category was inappropriate and did harm, and that it is important to balance the potential benefits of opioids with misuse and diversion risks. But the medical community still largely agrees that, for some patients, opioids provide benefits. Indeed, the Centers for Disease Control, the Federation of State Medical Boards, a 2011 report by the Institute of Medicine, and all applicable medical and government guidelines on prescribing opioids have reaffirmed that opioids may be appropriate for patients whose chronic pain isn’t resolved by other means.

Re-evaluating the use of opioids in long-term pain makes sense given recent history, but rushing to judgment before we do so can do real harm and risks violating a fundamental component of the right to health, including the right to adequate treatment for pain. In over 80 interviews with patients, physicians, and experts, a recent Human Rights Watch report found a disconcerting trend: chronic pain patients are being forced off opioid medications simply because doctors fear regulatory oversight and reprisal. In many cases, physicians acted against their better medical judgment. Even when they believed their patients’ health was improved by long-term opioid treatment, they felt they had no option but to reduce patients’ doses dramatically or cut them off completely. They felt a wide range of pressures, from fear of Drug Enforcement Agency or state medical board scrutiny to the heavy bureaucratic burden created by insurance companies through their efforts to discourage opioid prescribing.

When deprived of their medication, the consequences for patients can be devastating: their health declines to the point where they can no longer work, do simple chores, or take care of their personal hygiene. Several patients said they had turned to alcohol or illicit drugs to manage their pain when they were deprived of care.

Take Maria Higginbotham, whose story is included in the report. She has undergone 12 operations to prevent the collapse of her spine. Unfortunately these operations, which failed to relieve her pain, also left her with adhesive arachnoiditis, an incredibly painful condition that causes the nerves of the spinal cord to “stick together.”

“Re-evaluating the use of opioids in long-term pain makes sense given recent history, but rushing to judgment before we do so can do real harm and risks violating a fundamental component of the right to health.”

Maria is now being forced to a lower dose of medication by a provider who believes she needs opioids, but is afraid of attracting law enforcement scrutiny of his practice. Previously, Maria could function independently; she now requires assistance to go to the toilet. To suggest that Maria has no legitimate right to these medications—and that her need for them is misguided, inappropriate or the result of drug misuse — is stigmatizing to all patients like her.

Hundreds of leading physicians and experts from with varying views on the efficacy of opioids have called attention to the dangers of involuntarily discontinuing opioids for the estimated 18 million Americans who currently use them for long-term pain, a practice the CDC and other medical bodies do not encourage. These dangers include medical destabilization, the lost ability to work and function, and suicide. The National Council on Independent Living (NCIL), a national disability rights organization, shares these concerns, which have a disproportionate impact on people with disabilities living with chronic pain who already face major barriers to accessing healthcare. The American Medical Association has similarly criticized the indiscriminate discontinuation of opioids, and has underscored that the stigma surrounding opioids now affects cancer and palliative care patients who, despite explicit exemptions, face increased barriers to access as well.

While liberal prescribing undoubtedly caused harm, further perpetuating inflammatory and stigmatizing ideas about people who rely on opioids helps legitimize the growing reluctance of physicians to prescribe these medications to those who they believe need them. At a time when the prescribing of opioids has dropped precipitously and drug overdose deaths are largely attributed to illicit substances, such harm ought to figure into the conversation.

It’s true that there is a lack of high quality data studying the efficacy of opioids beyond 12 weeks, but it is also the case that most medications approved for the treatment of pain reflect studies of similar duration. This is in part because doing long-term, placebo-controlled trials with real human beings who are suffering presents practical and ethical challenges.

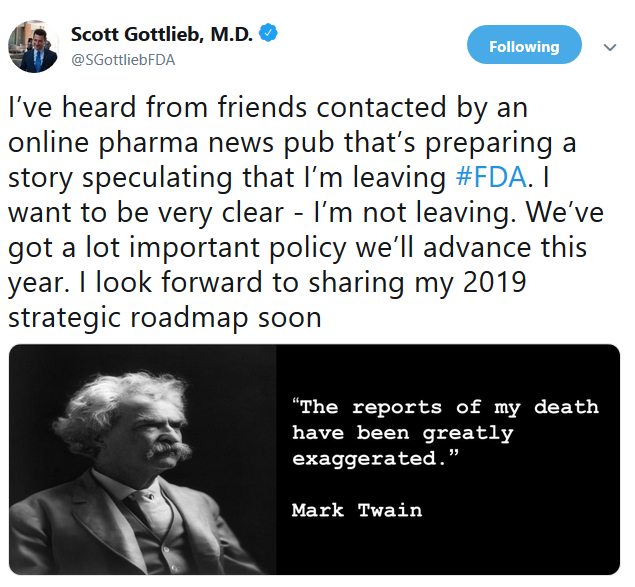

FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb recently responded to the concerns raised by 60 Minutes, by announcing that the agency will conduct new studies into the efficacy of opioid analgesics for chronic pain, a move that he signaled could have an impact on how these drugs are marketed in the future. We agree that more research is critical and have backed initiatives such as the National Pain Strategy that call for much needed additional research into chronic pain. In the meantime, the dangers of reinforcing an incomplete or incorrect narrative and of stigmatizing patients are real—60 Minutes should ensure it doesn’t do either in its coverage, and should show all sides of the story.

This article was originally published on the Human Rights Watch website and is republished with permission.

Laura Mills is a health researcher at Human Rights Watch and author of the HRW report, “Chronic Pain, the Overdose Crisis, and Unintended Harms in the U.S.”

Kate M. Nicholson is a civil rights and health policy attorney. She served for 20 years in the Department of Justice’s civil rights division, where she drafted current regulations under the Americans With Disabilities Act. She gave a TEDx talk about chronic pain, “What We Lose When We Undertreat Pain.”

Lindsay Baran is the policy analyst at the National Council on Independent Living (NCIL), the longest-running national cross-disability grassroots organization run by and for people with disabilities.