Do Prescription Opioids Increase Social Pain and Isolation?

/By Pat Anson, PNN Editor

Long-term use of opioid medication may increase social isolation, anxiety and depression for chronic pain patients, according to psychiatric and pain management experts at the University of Washington School Medicine.

In an op/ed recently published in Annals of Family Medicine, Drs. Mark Sullivan and Jane Ballantyne say opioid medication numbs the physical and emotional pain of patients, but interferes with the human need for social connections.

“Their social and emotional functioning is messed up under a wet blanket of opioids,” Sullivan said in a UW Medicine press release.

Sullivan and Ballantyne are board members of Physicians for Responsible Opioid Prescribing (PROP), an influential anti-opioid activist group. Ballantyne, who is president of PROP, was a member of the “Core Expert Group” that advised the CDC during the drafting of its controversial 2016 opioid guideline. She has retired as a professor of pain medicine at the university, while Sullivan remains active as a professor of psychiatry.

In their op/ed, Sullivan and Ballantyne say it is wrong to assume that chronic pain arises solely from tissue damage caused by trauma or disease. They cite neuroimaging studies that found emotional and physical pain are processed in the same parts of the human brain. While prescription opioids may lessen physical pain, they interfere with the production of endorphins – opioid-like hormones that help us feel better emotionally.

“Many of the patients who use opioid medications long term for the treatment of chronic pain have both physical and social pain,” they wrote. “Rather than helping the pain for which the opioid was originally sought, persistent opioid use may be chasing the pain in a circular manner, diminishing natural rewards from normal sources of pleasure, and increasing social isolation.

“To make matters worse, the people who need and want opioids the most, and who choose to use them over the long term, tend to be those with the most complex forms of chronic pain, containing both physical and social elements. We have called this process ‘adverse selection’ because these are also the people who are also at the greatest risk for continuous or escalating opioid use, and the development of complex dependence.”

Sullivan and Ballantyne say doctors need to recognize that when patients have both physical and social pain, long-term opioid therapy is “more likely to harm than help.”

“We believe that short-term opioid therapy, lasting no more than a month or so, will and should remain a common tool in clinical practice. But long-term opioid therapy that lasts months and perhaps years should be a rare occurrence because it does not treat chronic pain well, it impairs human social and emotional function, and can lead to opioid dependence or addiction,” they wrote.

Angry and Depressed Patients

It’s not the first time Sullivan and Ballantyne have weighed in on the moods and temperament of chronic pain patients. In a 2018 interview with Pain Research Forum, for example, Ballantyne said patients often have “psychiatric comorbidities” and become “very angry” at anyone who suggests they shouldn’t be on opioids.

“I’ve never seen an angry patient who is not taking opiates. It’s people on opiates who are angry because they’re frightened, desperate, and need to stay on them. And I don’t blame them because it is very difficult to come off of opiates,” she said.

In a 2017 interview with The Atlantic, Sullivan said depression and anxiety heighten physical pain and fuel the need for opioids. “People have distress — their life is not working, they’re not sleeping, they’re not functioning,” Sullivan said, “and they want something to make all that better.”

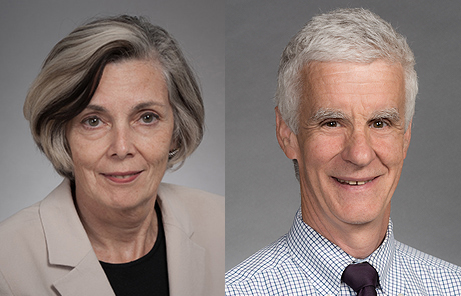

JANE BALLANTYNE MARK SULLIVAN

In a controversial 2015 commentary they co-authored in the New England Journal of Medicine, Sullivan and Ballantyne said chronic pain patients should learn to accept pain and get on with their lives, and that relieving pain intensity should not be the primary focus of doctors. The article infuriated both patients and physicians, including dozens who left bitter comments.

“Great job. I will be going into the coffin business thanks to these believers that people should suck it up. How NEJM even recognizes these people as doctors and not quacks is beyond me,” wrote a family practice physician.

“I take just enough narcotic pain meds to cut the edge off of my pain to be coherent enough to love my wife and respond to your constant misinformation,” wrote a patient.

Ballantyne and Sullivan’s op/ed in Annals of Family Medicine has yet to produce a similar response, either pro or con. The article was submitted to the journal over a year ago, but is only being published now.

Ballantyne disclosed in her conflict-of-interest statement that she has been a paid consultant in opioid litigation lawsuits, while Sullivan disclosed that he provided expert testimony for the states of Maryland and Missouri.

Other PROP board members have also found a lucrative sideline testifying in lawsuits. The organization is currently conducting a fundraiser to hire a new Executive Director to “take PROP's work to the next level.”