Tarantulas May Help Develop New Pain Medication

/By Pat Anson, PNN Editor

Venom from a bird-catching Chinese tarantula may hold the key to medications that could someday block pain signals in humans, according to a new study at the University of Washington School of Medicine. Researchers say the oversized, hairy spiders inject a toxin into the birds that quickly immobilize them.

"The action of the toxin has to be immediate because the tarantula has to immobilize its prey before it takes off," said William Catterall, PhD, a professor of pharmacology and lead author of a study published in the journal Molecular Cell.

Catterall and his colleagues were curious how the venom works, so they used a high-resolution cryo-electron microscope to get a clear molecular view of its effect on nerve cells.

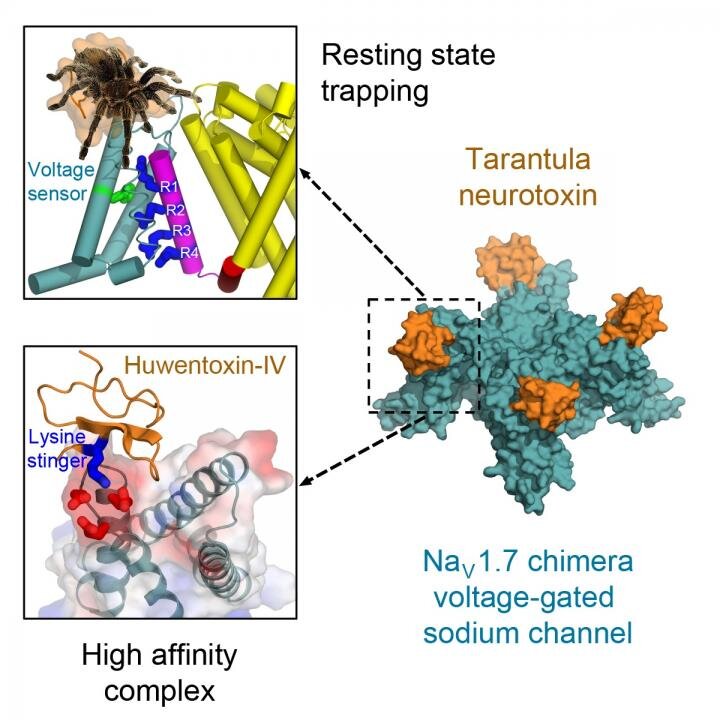

They found that tarantula venom contains a neurotoxin that locks the voltage sensors on sodium channels, the tiny pores on cell membranes that generate electric signals to nerves and muscles.

Locked in a resting position, the voltage sensors are unable to activate and the spider’s prey is essentially paralyzed.

"Remarkably, the toxin plunges a 'stinger' lysine residue into a cluster of negative charges in the voltage sensor to lock it in place and prevent its function," Catterall said. "Related toxins from a wide range of spiders and other arthropod species use this molecular mechanism to immobilize and kill their prey."

In humans, sodium channels known as the Nav1.7 channel are essential for the transmission of pain signals from the peripheral nervous system to the spinal cord and brain.

UNIVERSITY OF WASHINGTON

In theory at least, drugs modeled after tarantula venom could be used to target and immobilize the Nav1.7 channel. Previous research has shown that people born without Nav1.7 channels due to genetic mutation are indifferent to pain – so blocking those channels in people with normal pain pathways could form the basis for a new type of analgesic.

"Our structure of this potent tarantula toxin trapping the voltage sensor of Nav1.7 in the resting state provides a molecular template for future structure-based drug design of next-generation pain therapeutics that would block function of Nav1.7 sodium channels," Catterall explained.

While venom-based medicine may sound impractical and more than a little creepy, it’s not unheard of. A pharmaceutical drug derived from cone snail venom is already being used to treat chronic pain. Prialt is injected into spinal fluid to treat severe pain caused by failed back surgery, trauma, AIDS and cancer. Like tarantula venom, Prialt blocks channels in the spinal cord from transmitting pain signals to the brain.