Guideline Recommends Topical Pain Relievers for Muscle Aches and Joint Sprains

/By Pat Anson, PNN Editor

A new guideline for primary care physicians recommends against the use of opioid medication in treating short-term, acute pain caused by muscle aches, joint sprains and other musculoskeletal injuries that don’t involve the lower back.

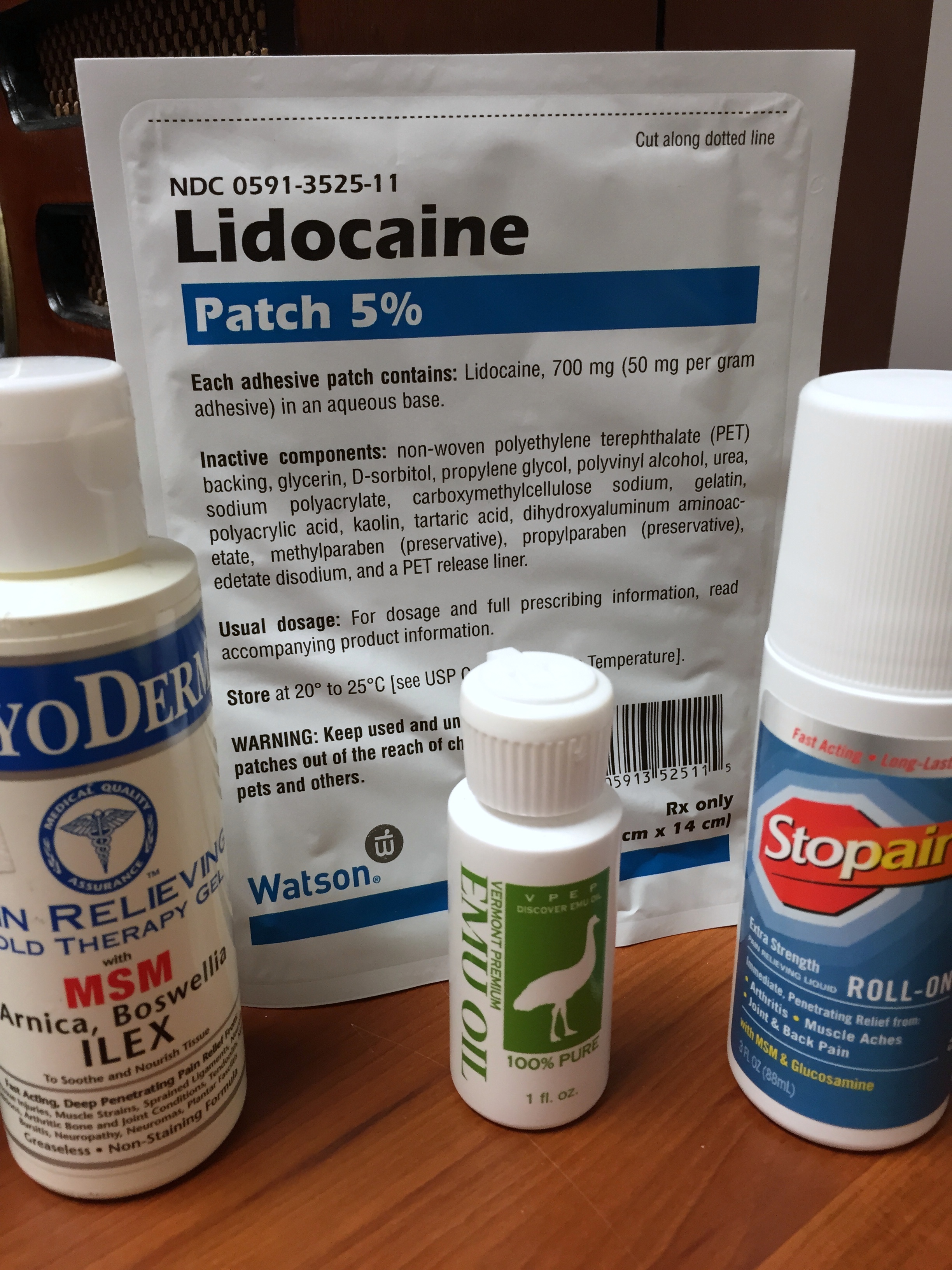

The joint guideline by the American College of Physicians (ACP) and the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) – which collectively represent nearly 300,000 doctors in the U.S. – recommends using topical pain creams and gels containing non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) as first line therapy. Other recommended treatments include oral NSAIDs, acetaminophen, specific acupressure, or transcutaneous nerve stimulation (TENS).

Musculoskeletal injuries, such as ankle, neck and knee injuries, are usually treated in outpatient settings. In 2010, they accounted for over 65 million healthcare visits in the U.S., with the annual cost of treating them estimated at over $176 billion.

"As a physician, these types of injuries and associated pain are common, and we need to address them with the best treatments available for the patient. The evidence shows that there are quality treatments available for pain caused by acute musculoskeletal injuries that do not include the use of opioids," said Jacqueline Fincher, MD, president of ACP.

Opioids, including tramadol, are only recommended in cases of severe injury or intolerance to first-line therapies. While effective in treating pain, the guideline warns that a “substantial proportion” of patients given opioids for acute pain wind up taking them long-term.

The new guideline, published in the Annals of Internal Medicine, recommends topical NSAIDs, with or without menthol, as the first-line therapy for acute pain from non-low back, musculoskeletal injuries. Topical NSAIDs were rated the most effective for pain reduction, physical function, treatment satisfaction and symptom relief.

Treatments found to be ineffective for acute musculoskeletal pain include ultrasound therapy, non-specific acupressure, exercise and laser therapy.

"This guideline is not intended to provide a one-size-fits-all approach to managing non-low back pain," said Gary LeRoy, MD, president of AAFP. "Our main objective was to provide a sound and transparent framework to guide family physicians in shared decision making with patients."

Guideline Based on Canadian Research

Interestingly, the guideline for American doctors is based on reviews of over 200 clinical studies by Canadian researchers at McMaster University in Ontario, who developed Canada’s opioid prescribing guideline. The Canadian guideline, which recommends against the use of opioids as a first-line treatment, is modeled after the CDC’s controversial 2016 opioid guideline.

After reviewing data from over 13 million U.S. insurance claims, McMaster researchers estimated the risk of prolonged opioid use after a prescription for acute pain was 27% for “high risk” patients and 6% for the general population.

"Opioids are frequently prescribed for acute musculoskeletal injuries and may result in long-term use and consequent harms," said John Riva, a doctor of chiropractic and assistant clinical professor in the Department of Family Medicine at McMaster. "Potentially important targets to reduce rates of persistent opioid use are avoiding prescribing opioids for these types of injuries to patients with past or current substance use disorder and, when prescribed, restricting duration to seven days or less and to lower doses."

Riva and his colleagues said patients are also at higher risk of long-term use if they have a history of sleep disorders, suicide attempts or self-injury, lower socioeconomic status, higher household income, rural residency, lower education level, disability, being injured in a motor vehicle accident, and being a Medicaid recipient.

A history of alcohol abuse, psychosis, episodic mood disorders, obesity, and not working full-time “were consistently not associated with prolonged opioid use.”

The McMaster research, also published in the Annals of Internal Medicine, was funded by the National Safety Council (NSC), a non-profit advocacy group in the U.S. supported by major corporations and insurers. The NSC has long argued against the use of opioid pain relievers, saying they “do not kill pain, they kill people.”