Tax on Prescription Opioids Costly for Pain Patients

/By Anastassia Gliadkovskaya, Kaiser Health News

Mike Angevine lives in constant pain. For a decade the 37-year-old has relied on opioids to manage his chronic pancreatitis, a disease with no known cure.

But in January, Angevine’s pharmacy on Long Island ran out of oxymorphone and he couldn’t find it at other drugstores. He fell into withdrawal and had to be hospitalized.

“You just keep thinking: Am I going to get sick? Am I going to get sick?” Angevine said in a phone interview. “Am I going to be able to live off the pills I have? Am I going to be able to get them on time?”

His pharmacy did not tell him the reason for the shortage. But Angevine isn’t the only pain patient in New York to lose access to vital medicine since July 2019, when the state implemented an excise tax on many opioids.

The tax was touted as a way to punish major drug makers for their role in the opioid epidemic and generate funding for treatment programs. But to avoid paying, scores of manufacturers and wholesalers stopped selling opioids in New York. Instead of the anticipated $100 million, the tax brought in less than $30 million in revenue, two lawmakers said in interviews. None of it was earmarked for substance abuse programs, they said.

The state’s Department of Health, which has twice this year delayed an expected report on the impact of the tax, did not respond to questions for this story.

The tax follows strong efforts by federal and New York officials to tamp down the use of prescription opioids, which had already cut back some supply. Now, with some medications scarce or no longer available, pain patients have been left reeling. And the law appears to have missed its target: Instead of taking a toll on manufacturers, the greater burden appears to have fallen on pharmacies that can no longer afford or access the painkillers.

Among them is Epic Pharma. Independent Pharmacy Cooperative, a wholesaler, confirmed it no longer sells medications subject to the tax, but still sells those that are exempt, which are treatments for opioid addiction methadone and buprenorphine and also morphine. AvKARE and Lupin Pharmaceuticals said they do not ship opioids to New York anymore. Amneal Pharmaceuticals, which manufactures Angevine’s oxymorphone, declined to comment, as did Mallinckrodt.

Since the tax went into effect, Cardinal Health, which provides health services and products, published an extensive 10-page list of opioids it does not expect to carry. Cardinal Health declined to comment.

The New York tax is slowly gaining attention in other states. Delaware passed a similar tax last year. Minnesota is assessing a special licensing fee between $55,000 and $250,000 on opioid manufacturers. New Jersey Gov. Phil Murphy proposed such a tax this year but was turned down by the legislature.

More Expensive Prescriptions

The company that makes the first point of sale within New York pays the tax. That isn’t always the drug maker. It can mean wholesalers selling to pharmacies here are assessed, explained Steve Moore, president of the Pharmacists Society of the State of New York.

Independent Pharmacy Cooperative (IPC) said about half its revenue from opioid sales in New York would have gone to taxes. Mark Kinney, the company’s senior vice president of government relations, said the law is putting companies in a very difficult position. When wholesalers like IPC left the opioid market, competitive prices went with them.

Without these smaller wholesalers, it’s hard for pharmacies to go back to other wholesalers “and say, ‘Hey, your prices aren’t in line with the rest of the market,’” Moore said.

Indeed, nine independent pharmacies told KHN that when they can get opioids they are more expensive now. They have little choice but to eat the cost, drop certain prescriptions or pass the expense along.

“We can trickle that cost down to the patient,” said a pharmacist at New London Pharmacy in Manhattan, “but from a moral and ethics point of view, as a health care provider, it just doesn't seem right to do that. It’s not the right thing to ask your patient to pay more.”

In addition, Medicare drug plans and Medicaid often limit reimbursements, meaning pharmacies can’t charge them more than the programs allow.

Stone’s Pharmacy in Lake Luzerne was losing money “hand over fist,” owner Leigh McConchie said. His distributor was adding the tax directly to his pharmacy’s cost for the drugs. That helped drive down his profit margins from opioid sales between 60% and 70%. Stone’s stopped carrying drugs like fentanyl patches and oxycodone, and though that distributor now pays the tax itself, the pharmacy is still feeling the effects.

“When you lose their fentanyl, you generally lose all their other prescriptions,” he said, noting that few customers go to multiple pharmacies when they can get everything at one.

If pharmacies have few opioid customers, those price hikes have less impact on their business. But being able to manage the costs is not the only problem, explained Zarina Jalal, a manager at Lincoln Pharmacy in Albany. Jalal can no longer get generic oxycodone from her supplier Kinray, though she can still access brand-name OxyContin.

New York’s Medicaid Mandatory Generic Drug Program requires insurers to provide advance authorization for the use of brand-name prescriptions, delaying the approval process. Sometimes patients wait several days to get their prescription, Jalal explained.

“When I see them suffer, it hurts more than it hurts my wallet,” she said.

One of Jalal’s customers, Janis Murphy, needs oxycodone to walk without pain. Now she is forced to buy a brand-name drug and pays up to three times what she did for generic oxycodone before the tax went into effect. She said her bill since the start of this year for oxycodone alone is $850. Lincoln Pharmacy works with Murphy on a payment plan, without which she would not be able to afford the medication at all. But the bill keeps growing.

“I’m almost in tears because I cannot get this bill down,” she said in a phone interview.

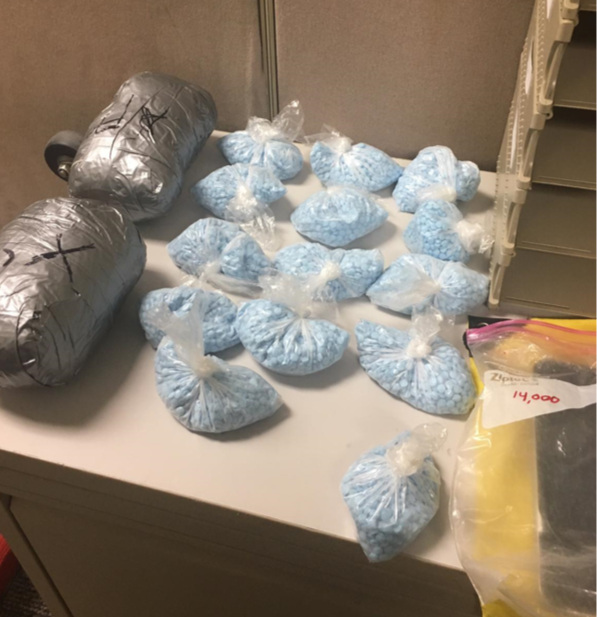

Several pharmacists raised concerns that patients who lose access to prescription opioids may turn to street drugs. High prescription prices can drive patients to highly addictive and inexpensive heroin. McConchie of Stone’s Pharmacy said he now dispenses twice as many heroin treatment drugs as he did a year ago. Former opioid customers now come in for prescriptions for substance use disorder.

Cost of Percocet Doubled

Trade groups and some physicians and state legislators opposed the tax before it went into effect, voicing concerns about a slew of potential consequences, including supply problems for pharmacists and higher consumer prices.

New London Pharmacy said one of its regular distributors stopped shipping Percocet, a combination of oxycodone and acetaminophen. Instead, the pharmacy orders from a more expensive company. The pharmacist estimated that a bottle of Percocet for which it used to pay $43 now costs up to $92.

“Even if we absorb the tax, we’re not getting a break from reimbursements either,” a pharmacist who spoke on the condition of anonymity explained, adding that insurance reimbursements have not increased in proportion to rising drug costs. “We’re losing.”

Latchmin Raghunauth Mondol, owner of Viva Pharmacy & Wellness in Queens, has also seen that problem. The pharmacy used to be able to purchase 100 15-milligram tablets of oxycodone for $15, but that’s now $70, she said, and the pharmacy is reimbursed only about $21 by insurers.

Other opioids are just not available.

Mondol said she has been unable to obtain certain doses of two of the most commonly prescribed opioids, oxycodone and oxymorphone—the drug Angevine was on.

After Angevine lost access to oxymorphone, his doctor put him on morphine, but it does not give him the same relief. He’s been in so much pain that he stopped going to physical therapy appointments.

“It’s a marathon from hell,” he said.

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a nonprofit news service covering health issues. It is an editorially independent program of KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation) that is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.